At six years old, Isabella Potì would walk through the Białowieża Forest Reserve in Poland with a glass bottle in her hand. She was heading to a barn, where she’d collect warm milk straight from a cow and carry it home to drink immediately. Then she’d collect eggs directly from the hens. Her grandparents taught her to eat raw eggs, as generations had before her. No distance from the source. No comfort in between.

Υears later, Potì, executive chef and co-owner of Bros’ in Puglia, watches her four-year-old son cut into a langoustine at the Michelin-starred restaurant. Then he eats sweetbreads without flinching.

This raw relationship with food, not romanticized, not Instagram-friendly, but real, is the DNA of Bros’. And it’s exactly what most people refuse to understand. “We are not a comfort food restaurant,” Potì said. “We are funny, we are letting you think about what your dish was. We are anything but comfortable.”

It’s a philosophy that sets her apart from Italy’s traditional culinary scene. The Michelin star came when she was in her early twenties. But success didn’t mean stability.

December 2021. A table of Americans sat in the dining room of Bros’ in Lecce, the city in Salento where Potì and her partner, Floriano Pellegrino, had opened their restaurant five years earlier. They were probably expecting Italian food, lasagna, or homemade pasta. Instead, they got avant-garde.

A travel blogger at the table wrote about the experience. She wasn’t a food critic, but Potì said she wrote well. She used careful language to express her dissatisfaction. She built tension. The review went viral.

“It was a normal night,” Potì said, unbothered. “It happens sometimes. People make mistakes when choosing a restaurant. They had a different perspective of looking at Italian food.”

Where most chefs would panic, Potì saw opportunity. “One of our friends called us,” she said, “and kept saying that we purposely did that to gain popularity. We said that it wasn’t, but we truly took this negative criticism and re-directed it to something bigger.”

The New York Times came to Lecce. Not to judge, Potì emphasized, but to understand. What kind of restaurant inspired such visceral reactions? People started flying to Puglia out of curiosity, to see what went wrong, what went right. “They were leaving happy,” Potì said. “So that worked perfectly.” For Bros’ Trattoria, bad publicity became an American debut without ever leaving Italy.

But there was a problem the viral moment couldn’t fix: Bros’ was dying financially. “In the beginning, we did some really bad business choices,” Potì admitted. The restaurant occupied a tiny space in the center of Lecce at a massive rent. They were paying huge amounts from their own pockets. “The space wasn’t that comfortable,” she said. “It was time for a change.”

The Michelin star had felt like validation. “That was one point that we were going in the right way,” she said. “But still, there was a long way to go.” The pressure was immense. The star brought expectations but not necessarily profit.

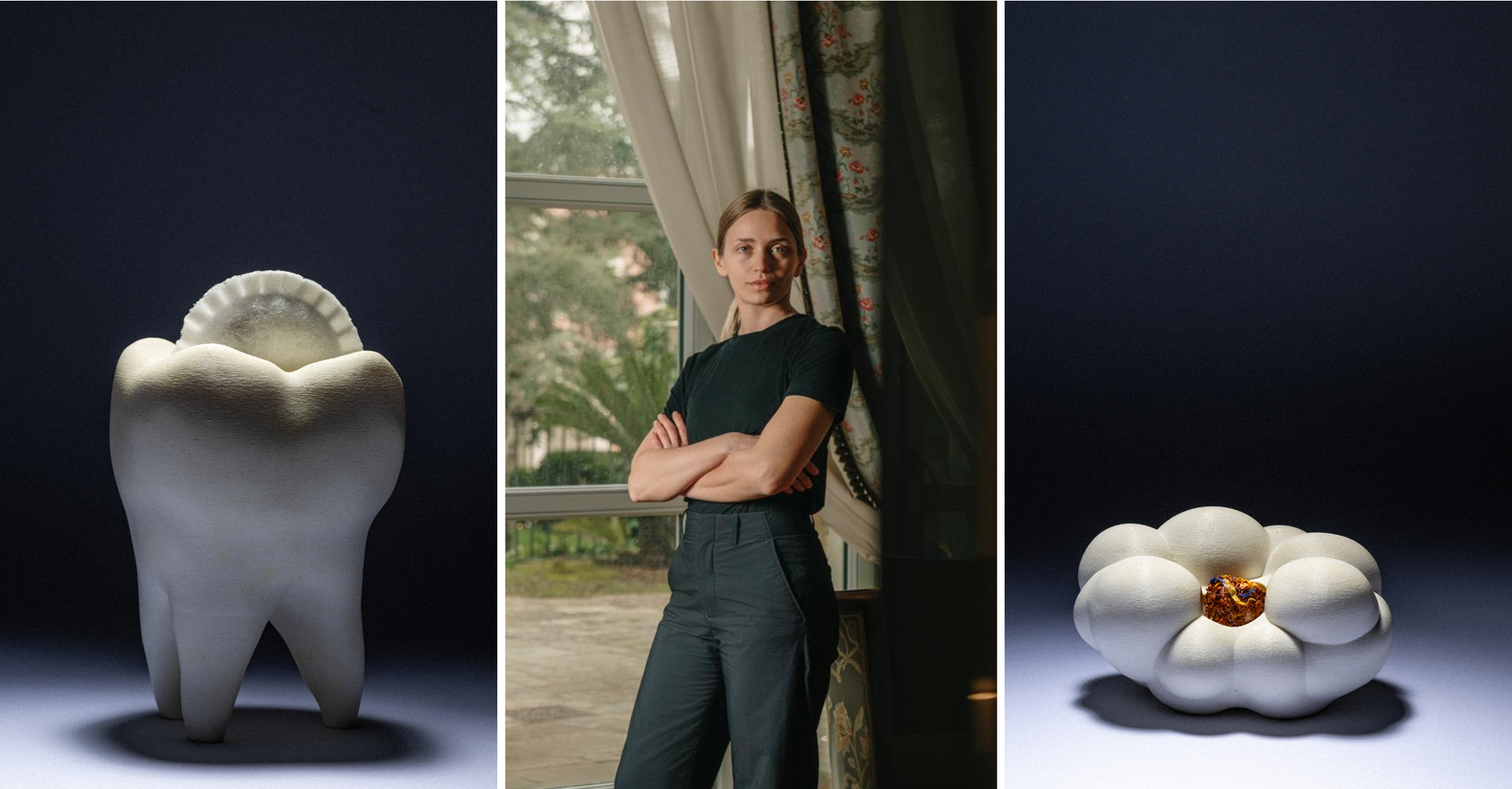

Isabella Potì & Floriano Pellegrino

“I think that part of Puglia was still emerging as a culinary destination,” Potì said. “It was easier for us here in the North of Puglia to find the right tourism and the right start.” In 2024, they made the decision: close the Lecce location and reopen in Martina Franca, nearly 100 kilometers north in the Valle d’Itria. They’d built something people recognized, something people traveled for, and now they had to trust those people would follow them to an entirely new location. “The people who made our restaurant what it is today remained our clients,” Potì said. “The best part was that they moved with us.”

The new Bros’ sits at Relais Villa San Martino in Martina Franca, in northern Puglia. It’s a Villa with 21 rooms. A team of approximately 30 people. A kitchen with actual space. “We were looking for bigger places, and we found this amazing place, with great people around,” Potì said. “They were our clients first, and we ended up working with them. We truly matched our necessities.”

The change shows in everything. There’s room for the multi-step dining experience they’d always envisioned but couldn’t execute in the cramped Lecce space. “We were a little bit more relaxed,” Potì said, “even if we had more things to think about. But this didn’t stress us. We found out what the main focus of our restaurant was.”

Potì’s dual heritage shaped that focus. Half Polish, half Italian, she grew up between two culinary worlds, the raw, unromanticized relationship with food from Poland, and the Sunday lasagnas of her Italian grandmother. The focus, it turns out, wasn’t just the food. It was the philosophy behind it. The willingness to make people uncomfortable. The insistence on discovery over familiarity.

Right now, Bros’ is aiming for more stars, expansion beyond Italy. The move to Villa San Martino wasn’t an ending; it was a strategic repositioning.

The woman who turned a bad review into an American introduction, who closed a successful restaurant to save it, who learned to eat raw eggs in a Polish forest, and now raises her children in the same raw relationship with food, she’s already proven she doesn’t operate by conventional rules.

Comfort, after all, is the one thing Potì is refusing to serve.

Images: Brand respectively